Elsie de Wolfe is a Great Lady Decorator.

I’m reading a wonderful book, The Great Lady Decorators, The Women Who Defined Interior Design, 1870-1955, by Adam Lewis. There are a dozen, but don’t worry, I’m only going to cover a few and not all in one post!

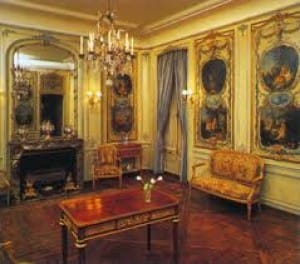

Elsie de Wolfe was the first professional interior designer in America. Until Elsie came on the scene, well to do women used the services of curtain makers, furniture salesmen, wallpaper specialists, and other craftsmen and did their own decorating. Elsie De Wolfe, who believed in achieving a single, harmonious, overall design statement, felt that the decoration of the home should reflect the woman’s personality, rather than simply the husband’s wealth, saying, “It is the personality of the mistress that the home expresses. Men are forever guests in our homes, no matter how much happiness they may find there.” She did away with the heavy, dark, stuffy style of the Victorian era and introduced a palette of pale colors and a lighter, refreshing style. Having spent summers abroad, she was influenced by the light, gilded interiors of Versailles and the delicate eighteenth-century French furniture.

She became a designer in her forties after starting a career as an actress, which was frowned upon by members of polite society. She had no other choice. Her father had died when she was 25, leaving her, her mother and 4 siblings almost penniless, and her mother possessed no professional skills. Facing the reality of the situation, she reportedly said, “I loathe poverty.” She did not achieve success in the theater. One of the most famous anecdotes recalls two women leaving the theater when one asked the other, “What did you think of de Wolfe?” The other replied, “I liked her dress in the second act better than what she wore in the first act.” It must have pained her to see her understudy, Ethel Barrymore, go on to an distinguished career. This may have influenced de Wolfe’s decision to retire from the stage and launch herself as a professional interior designer around the turn of the century. She had cards printed with her logo, a wolf holding a flower in its paw, and opened an office in New York City.

Luck, timing and the support of influential people helped contribute to her success as a designer. She had the good fortune, at 18, to attend school in Scotland, live with relatives, and be presented at court in London. She knew she wasn’t a beauty: her forehead was too long and she had beady eyes. But, dressed in her presentation gown with its flowing train, she realized that a woman need not be pretty. Wearing a flattering gown suitable for her figure and the occasion, a woman could reflect an aura of beauty. The confidence she gained at that moment changed her future life and I suspect it was about that event she said this: “I was not ugly. I might never be anything for men to lose their heads about, but I need never again be ugly. This knowledge was like a song within me. Suddenly it all came together. If you were healthy, fit, and well-dressed, you could be attractive.”

In the 1880’s Elsie met Elizabeth Marbury from one of the wealthiest, most socially prominent New York families. They summered together for five years and moved into a house together in New York and remained life-long friends and companions. At the turn of the century it was not acceptable for women to stay alone in a hotel, which became a serious problem as women began to move about more freely in society. Enter the concept of the Colony Club-a club for women similar to the men’s clubs in London. Architect Stanford White was commissioned to design the club but made it clear that he would not be responsible for the interior decorations. Marbury, one of the founding club members, secured the commission for Elsie. The architect was asked for his opinion and his response was, “Give the job to Elsie and leave her alone. She knows more than any of us.” To research the designs for her first large commission, she sailed to England and brought back flowered chintz (then considered an inexpensive, countrified fabric) and simple furniture. Bedrooms were thought to be all about sleeping. Elsie made them all about rest and comfortable living. There was a dressing table next to a window to afford natural light when applying makeup. There was a comfortable reading chair and lamp, and a bedside table with a lamp and room for a book and writing pad. De Wolfe’s bedroom furnishings set a standard for gracious living that is upheld even today. Her success with the Colony Cub assured future demand for her services and her business flourished. She gave lectures. She wrote a book, The House in Good Taste, she was commissioned to decorate rooms in the Henry Clay Frick Fifth Avenue mansion, and she became a wealthy woman, making over a million dollars! Her maxim became “simplicity, suitability, and proportion.”

The reports about the poison gases and trench warfare during the war in France in 1914 was devastating for de Wolfe and she sailed for France in 1916 to volunteer in a hospital for burn victims. She performed the most menial of tasks to help care for the wounded. Following the war, she was fascinated with the cafe society of Paris, Vienna and the French Riviera and she joined a more frivolous circle of friends which included Elsa Maxwell, Cole Porter, Elsa Schiaparelli, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. She became the Duchess’ decorator and advised her on everything from what to wear to how to entertain.

Elsie de Wolfe and her style were changing. She began using bright, contemporary colors instead of her signature beige, mauve and gray [which we also like at Casart wallcovering]. She introduced leopard and zebra print chintz and even replaced blanket covers on beds with fur throws. She continued to surprise contemporaries with her innovations. She was probably the first woman to dye her hair blue, to perform handstands to impress her friends, and to cover eighteenth-century footstools in leopard-skin chintzes.

In 1926, stating she was 60 (but perhaps older), de Wolfe shocked everyone and deeply hurt Marbury by marrying Sir Charles Mendl. Some speculated she desired the title of Lady Mendl. Others suggested a more plausible reason. Diplomats and their families do not pay taxes when residing in a foreign country and Sir Charles was a minor diplomat. By marrying him, she no longer had to pay French taxes on her properties there. She and her husband kept separate apartments and had what would be considered an “open” marriage today. In 1935, before the outbreak of World War II, Parisian couturiers named Elsie de Wolfe, Lady Mendl, the Best Dressed Woman in the World. What a coup for a woman who was dressed in gray woolens and black stockings as a child!

In 1937, due to mismanagement by her brother, Elsie was forced to close her business and declare bankruptcy. The Mendls fled Europe during the war and settled in California and New York. But before leaving, Elsie threw a Circus Ball. Acrobats, clowns, jugglers and the like provided entertainment, but the star was Lady Mendl, who arrived riding an elephant.

Following the war, when Elsie returned to France, she was too old to work and sold her name at a profit, licensing her name to commercial enterprises. She died four years later. The obituaries reported that she was 85, but she was actually closer to 90 or 95. Diana Vreeland, in the preface to Jane Smith’s biography of de Wolfe wrote, “I adored Elsie de Wolfe. She was a marvelous woman with tremendous taste and a great sense of humor. She was a part of international society, but she never stopped being completely American-a working woman- and she was the most fantastic businesswoman there ever was. She was greedy, the way people in love are greedy, for more. She loved life and people, and fun and novelty, and she was never anything but her own self.”

Sir Charles died three years later and his ashes were taken to Pere Lachaise, the famous Paris cemetery, to be placed with Elsie’s, but Elsie’s ashes were gone. The rent on her crypt had not been paid in several years and it was never known where her ashes had been dumped when they were removed.

– Lorre Lei

Leave a Reply